PrintyMed artificial spider silk around a spool

Kristaps Jaudzems, professor at the University of Latvia and head of the Laboratory of Structural Biology and Drug Design at the Institute of Organic Synthesis, began his journey through spider webs about 10 years ago, when his team began researching how silk is formed in a spider’s body.

“We were interested in what molecular mechanism ensures the transition of the liquid raw material in the spider’s gland – to solid fibers, which have surprisingly impressive mechanical properties,” says Kristaps.

The research continued slowly, but successfully – armed with an understanding of the determining factors of this process, five years ago Kristaps applied his team to a project co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund for the development of a technology that would artificially imitate the natural production of spider silk in the laboratory. “While implementing the project, we successfully developed our method, where the biochemical mechanism that occurs in the spider is combined with an additional step of chemical modification – as a result, we can change the properties of the obtained artificial spider silk in a much larger range than the spider itself is capable of.”

When the project was almost finished, Kristaps decided to join the Commercialization Reactor – Latvian startup ecosystem organization that deals with the commercialization of science, training scientists and entrepreneurs on the operation of startups. Twice a year, the Commercialization Reactor organizes an Ignition Event – where scientists can present their research and its potential applications, while entrepreneurs listen and apply to cooperate with those whose ideas have fascinated them – then forming a company and trying to bring the invention to market. “My presentation was very popular, and three business teams were formed around the spider silk research,” says Kristaps. “Each of them pursued a different use – in the fields of transport, defense, and medicine. Currently, the activity of the others has stopped, but the established medical startup – PrintyMed – is developing rapidly, and we are trying to attract investors.”

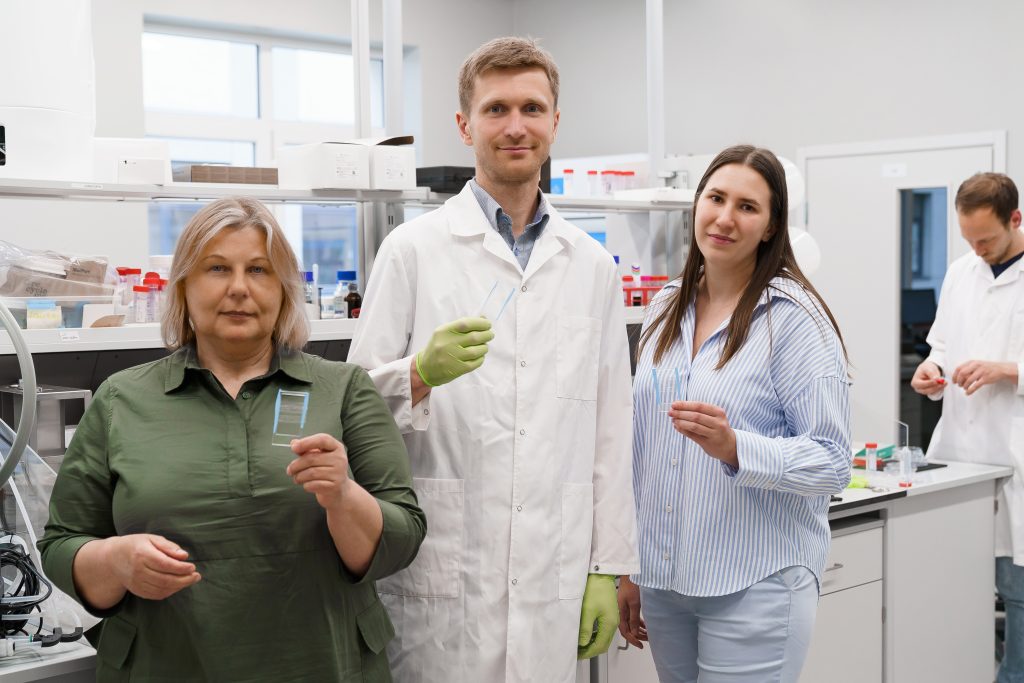

PrintyMed founders, from the right: Sandra Treide, Chief Medical Officer; Kristaps Jaudzems, Chief Technical Officer; Jekaterina Romanova, Chief Executive Officer

In search for the best use case

PrintyMed is in a somewhat unusual situation in the field of startups – although the technology is valuable, the team is working on developing its applications, especially looking at how changes in the prototyping process affect the result. “To a certain extent, we will be subject to what the material’s properties will be when we decide that we have reached the chemical composition we want to stick with in the near future,” explains Kristaps.

One of the main factors important for the material of spider silk is its interaction with tissue – ideally, it would not be dangerous to the body, nor would it cause an immune reaction that would break it down too quickly. The biodegradation time should be average – enough time for it to function as the structural basis for tissue regeneration or artificial organ cells, but also for it to be absorbed by the body afterward.

There are several potential applications that are still being prototyped, but it is difficult to predict which one will provide PrintyMed with a breakthrough that will help the startup stabilize financially. In addition, as with all medical technology innovation, these prototypes require in-depth research in a laboratory, as well as in pre-clinical studies – before they can even be tried in practice. “Our biggest goal is to adapt the material for 3D printing, so that any structures can be quickly and easily printed for tissue regeneration or the creation of artificial organs. However, for now, we have to look at the near future,” says Kristaps.

With the now mature idea, the team has joined several business incubators, the largest of which is right next door, in Estonia – Health Founders. A new chapter in PrintyMed began there, as a heart surgeon with 18 years of experience – David Yakobi from Israel – applied to be their mentor.

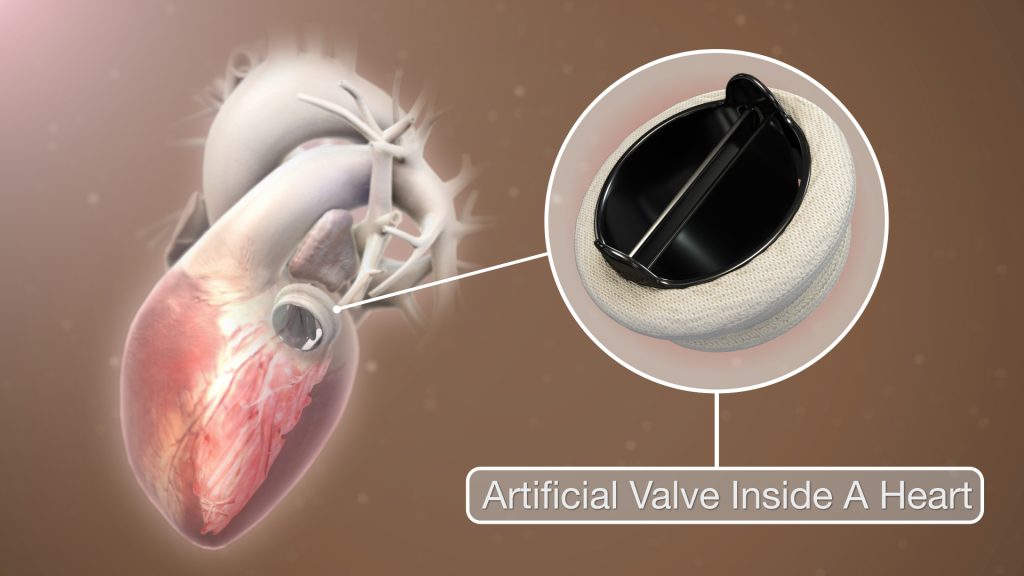

https://www.scientificanimations.com/wiki-images/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=96652114

Spider silk in the heart

«In 2019 I made a decision to spend more time with my family”, says David Jakobi. “Until then, I was extremely busy – operating on both adults and children, not only as a cardiac, but sometimes also a thoracic and oncology surgeon, as well as leading the ECMO team. I decided to slow down with surgery and focus more on work that would make my life more flexible – and I chose medical technology innovation. During these four years, I have met hundreds of startup teams, and new technologies have completely captivated me. PrintyMed is a great example – when I heard about their ambitious idea and exciting approach, I immediately decided that I wanted to work with them. Especially because I realized that my experience as a heart surgeon will help a lot.” Since Dr. Jakobi’s involvement, the focus of activity has largely shifted to the creation of artificial heart valves.

When a patient has a heart valve problem, there are several ways a doctor can help him, says Dr. Jakobi. First, it is necessary to assess whether surgery is necessary. Although drug therapy cannot cure the problem, it can relieve the symptoms. If surgery is still necessary, there are two options – ideally, the existing tissue should be kept and the valve repaired, but if the problem is too severe, it should be replaced.

Currently, there are two main types of artificial heart valves – mechanical and biological. The mechanical valve is made of carbon fiber and is very durable (would last more than 200 years in the body). However, blood clots can form on it, which then break off and cause serious problems (for example, if they end up in the limbs or the brain). This means that patients must take anticoagulants – usually vitamin K antagonists – which have severe side effects (e.g., spontaneous bleeding).

On the other hand, the biological valve is made from pig or cattle tissue – but rapidly degrades within 8-15 years. Additionally, they must be properly stored, usually in glutaraldehyde, which must be thoroughly rinsed before implantation and causes calcification.

A mechanical valve is often chosen for younger people to avoid the need for repeated operations – but unfortunately they have to take anticoagulants for the rest of their lives. On the other hand, biological ones are chosen in the case of older patients with the hope that it will last until the end of the patient’s life, which is not guaranteed. If a solution could offer a mechanical valve-like solution – sufficiently thin, durable, flexible and biocompatible – that does not require the use of medication, then there would be a huge demand in the market.

The scale of spider silk

Looking to the future

“There is still a long way to go before organ printing,” says Dr. Jakobi. “I believe it is possible, but until then we have to focus on what can actually be done in the near future, and I see the creation of a heart valve as such a real reference point that would practically demonstrate the power of artificial spider silk technology. But who knows, maybe it will be so effective that all plans will change. Replacing heart valves is a billion-euro market – each of them costs between 1000 and 7000 euros in Western countries.”

Moving forward requires pre-clinical (pig and sheep) and clinical studies, which in turn require increased production rates from lab facilities with bioreactors. In bioreactors, the spider’s genes are inserted into bacterial cells, which begin to produce the raw material silk – to be eventually separated from the bacteria. On the plus side, no new technology is needed to scale this process up. Kristaps hopes that for cooperation with the Latvian Biomedical Research and Study Center, where it will be possible to increase the currently obtained few grams of material in one batch – to up to tens or hundreds of grams. For further expansion of production, it will be necessary to cooperate with foreign biochemical production plants.

Dr. Jakobi invites: “I want to reach out to any doctor who has noticed an unmet need in medicine (perhaps a torn anterior cruciate ligament, or a meniscus problem, or a need to implant tendons, or cover the brain after cranial surgery, etc.) that could be solved with the help of spider silk, contact us! Maybe we can cooperate.”

This article was created in partnership with Medicus Bonus – a Latvian magazine for healthcare professionals – in a new series about healthcare innovation happening in Latvia. If you are a doctor, the subscription is free – just write to redakcija@medicusbonus.lv !